|

|

|

Cleveland Municipal Stadium

The Lady on the Lake.

The Home of the Browns and Indians. A wonder of the world. These

were all terms used to describe Municipal Stadium in it’s tenure. From

it’s construction in the 1930’s to it’s demolishment in the 1990’s, the phrase,

“It’s amazing” has been used by almost every spectator and event participant

that has ever

Ground was first broken on the facility in 1930, although the idea behind the stadium had been around for years. Up until the grand opening of the now famous complex, most major outdoor events such as football, baseball, boxing, and conventions were held in League Park on Lexington Ave and E. 66th. High school football was the biggest show of that day in the area (along with the Indians), and there was a definite shortage of fields for teams to compete. Proposals for a new downtown field were continually shot down in the 1910’s and 1920’s. Floyd A. Rowe, a city schools employee, first recommended a new 20 to 25 thousand-seat stadium to accommodate local needs. However, none of this ever came to fruition as slow moving politics and red tape kept delaying planning. All of this came to an end, though, when Clevelanders passed a $2.5M bond for a new “fireproof” stadium, proposed for a lakeside site that currently had a water-soaked dump occupying it. This bond passed 60% to 40% (a 55% approval was required for a ballot bond).

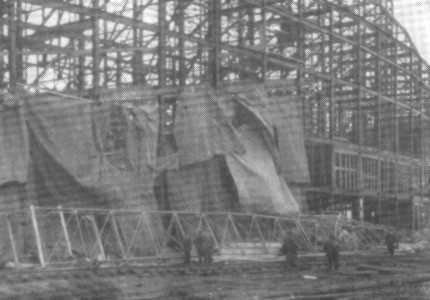

The original need for a 20,000 seat complex evolved into Cleveland Stadium. All in all, it took over 3 million bricks, 70 miles of electrical wire and conduit, and 4600 tons of steel. Official groundbreaking ceremonies were held on June 24, 1930. These ceremonies were held without much fanfare, as the city was not looking forward to this astronomical new expense. Construction would take just over one year to complete.

Stadium construction was completed by the time dedication ceremonies were held on July 1, 1931. Over 77,000 people went to that event, and either paid a quarter or 50 cents to get in. These ceremonies preceded the first official event ever in the stadium, a boxing match, by two days.

On July 3 of the same year, William L. Stribling was set to challenge Max Schmelling for boxing’s heavyweight championship. It was estimated that over 100,000 fans would attend the match. Based on those figures, there would be well over $1 Million in gate receipts. That wasn’t to be, though, as less than 40,000 people came out to see the contest and the fight lost money, although only by a small margin. Other events such as the Shriners and Grand Summer Opera Week continued to keep Municipal Stadium filled throughout 1931.

It wasn’t until July

31, 1932 that the Indians finally utilized this massive monument. The

Tribe was set to move in on July 14th, but negotiations broke down

and the first home stand on The Lake was delayed two weeks. Nevertheless,

over 80,000 fans came out to see the Indians take on the Philadelphia Athletics.

That figure set the all time Major League record for attendance. The Indians

lost that one game 1-0, as Philly 2B Max Bishop recorded the first ever hit.

The Indians continued to play in Municipal Stadium for another 61 years until

the new “Gateway” project opened up for baseball in 1994. The Indians

began their farewell tour that year as the baseball  at the stadium was commemorated by promotions, fanfare,

and anticipation of a new home.

at the stadium was commemorated by promotions, fanfare,

and anticipation of a new home.

The Cleveland Rams were the first football team to don the stadium. The rather unsuccessful Rams had begun operations in 1938, and had never played better than .500. The team suspended operations in 1943 due to WWII, but finally put a good season together in 1945, and found themselves playing for the NFL title against Sammy Baugh and the Washington Redskins at the stadium. The Rams won the contest, but continued to lose money in the city of Cleveland. Team owner Dan Reeves announced his plans to move the team from Cleveland to Los Angeles shortly after the season.

That suited Mickey

McBride just fine. McBride, a taxi company owner in Cleveland,

was going through with plans for a new football team in Cleveland that would

play in the NFL rival AAFC.

McBride had counted on the Rams and his team sharing the stadium during the

season, but the AAFC’s  Saturday games would not have made this scheduling impossible.

When Reeves backed out of the city in ’45, that gave McBride a football monopoly

in the city. The new team, eventually called the Browns, gained popularity

with the city quickly, and started an unrivaled tradition that remains to this

day.

Saturday games would not have made this scheduling impossible.

When Reeves backed out of the city in ’45, that gave McBride a football monopoly

in the city. The new team, eventually called the Browns, gained popularity

with the city quickly, and started an unrivaled tradition that remains to this

day.

Cleveland Stadium continued to be operated by the city through the 1970’s, and continued to lose money for the city. That’s why, in 1975, they happily gave full management control to Browns owner Art Modell. In his contract with the city, Art Modell would be responsible for over $100M in renovations through 1999, and would absorb all operating losses that the building may produce. Modell also agreed to give the city a cut of any profits of the time. It was a good deal for the city, and Modell considered it a good deal for him as well. He created the Cleveland Stadium Corporation (Stadiumcorp). He believed that he could not only eliminate debt, but generate profit as well. Modell meticulously managed the stadium, with help from Stadiumcorp’s employees, and continued to cut losses (although he rarely turned a profit) more than the city ever hoped to do.

Cleveland Stadium began to show it's age in the '70's. The building overall was in bad repair. The masonry had mold growing on it. The bathrooms were deemed too few, too old, too dirty, and too crowded. The locker rooms and clubhouse areas were cramped and smelled of mildew. People often came to the stadium and simply said, "it's amazing."

This amazement finally resulted in the Indians threatening to leave in the '90's, and cashing in on that threat with a bran new stadium. Modell, always able to keep his head above water with the stadium, wasn't able to any longer. Modell leased the stadium to the Indians (since he managed it), and the Tribe, with 82 home games, was Stadiumcorp’s biggest customer. Modell continued to try and manage the stadium, but didn’t have nearly the same success he had with the Tribe on board. As city officials continued to drag their feet on a stadium renovation package that would modernize the facility, the owner of Stadiumcorp continued to mismanage his money and get bad advice from his executives. This situation all came to a head in 1995, and in a desperation maneuver, Modell announced plans to move the team to Baltimore.

The Browns, in the

middle of their season, became distracted by these events, and instead of the

brouhaha that was the Indians last se ason

in Municipal Stadium, the Browns began a “Trail of Tears” so to speak.

They lost 7 of their final 8 contests, all coming after the announcement, and

finished the season 5-11. The only win they salvaged was the final

home game, a 26-10 win over Cincinnati. As the game ended, the crowd began

ripping out seats, bricks, wood, and anything else they could carry to remember

the Browns and the Stadium by. Browns players sadly embraced members of

the crowd, as they knew that this was goodbye forever.

ason

in Municipal Stadium, the Browns began a “Trail of Tears” so to speak.

They lost 7 of their final 8 contests, all coming after the announcement, and

finished the season 5-11. The only win they salvaged was the final

home game, a 26-10 win over Cincinnati. As the game ended, the crowd began

ripping out seats, bricks, wood, and anything else they could carry to remember

the Browns and the Stadium by. Browns players sadly embraced members of

the crowd, as they knew that this was goodbye forever.

The life of Cleveland Municipal Stadium, once considered a wonder of the world, officially came to an end when the NFL announced that it would return the Browns (in the form of an expansion franchise) to Cleveland provided a new stadium was built for them. Demolition of the Lady on the Lake paved the way for Cleveland Browns Stadium.

Have your own memory of the stadium? Send it to us, and let us share it with all the other Browns fans around the world.

|